Why startups should be seen but not heard

Paddy Willis

During the 19th century it was a common expression among British parents that “children should be seen, but not heard”. Offspring would be tolerated as the heirs apparent but, until they had graduated from Oxford or Cambridge and could hold a conversation at dinner amongst erudite guests, most parents would outsource their development to nannies, tutors and governesses, occasionally being reacquainted at bedtime.

Perhaps there is a lesson for corporate venturing here?

Chief executives of corporate businesses are, after all, most interested in their venture startups once they scale and contribute to the parental bottom line. The challenge they face in the meantime is how to find and back exciting startup innovation before their competition does, and how to avoid their senior management skipping the day job to hang with the cool kids.

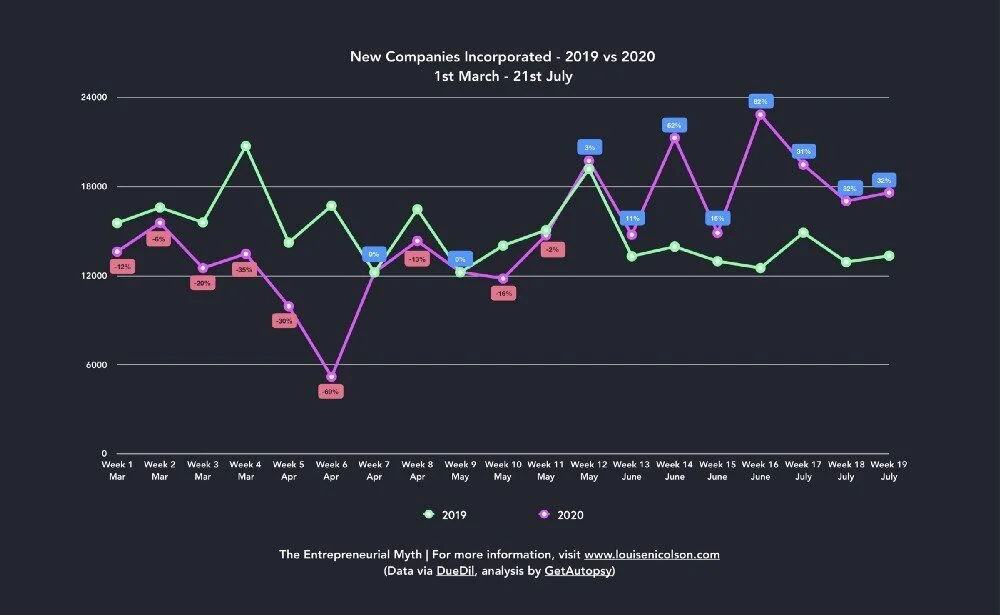

With necessity the mother of invention, how does the savvy corporate keep up with exciting new ideas? The UK has seen a surge in new business registrations this summer, with one week in June seeing an 82% increase over the same period in 2019. Overall, the figure sits at 22,863 so far in 2020 compared to 12,532 this time last year, according to GetAutopsy and DueDil. With the impact of the recession yet to fully land its blow, researchers will have their hands full when it comes to tracking the likely startup winners emerging in the coming years from this global pandemic, whilst their corporate treasurers count the cost to their own businesses.

New Companies incorporated - 2019 vs 2020 from “Necessity drives lockdown business creation” by Maryam Mazraei and Louise Nicolson

The consumer products group (CPG) sector, where our company Mission Ventures operates in food and drink, is no stranger to corporate venturing. Many of the world’s largest food groups have launched some form of activity in the past five years, reflecting the challenge of driving native innovation internally. Solutions range from fully in-house operations, often located in a WeWork to give a semblance of independence, to partnerships and variations on the outsource theme. One key difference for our sector is the time it can take to grow and scale a successful CPG brand compared, say, to a tech startup.

This July Mission Ventures announced a partnership with Warburtons, the UK’s largest baker and fifth largest food brand. Called Batch Ventures, this joint venture provides this fifth-generation family business with the sort of arms-length support for innovation that allows them to focus on being world-class at what they do at their core, without distraction from needy young startups. Being a team of exited entrepreneurs from the food sector ourselves, having launched and successfully exited disruptive brands like New Covent Garden Soup, Little Dish and Plum Baby, we are, in effect, the nannies and tutors to the next generation of baking-related food brands.

Startups in the food sector need, like children, time to mature from a teetering toddler to a thriving teenager. Management time is often the scarcest resource for a corporation measuring performance quarterly or annually, with little impact to be achieved in that regard from early investments in challenger brands. Given, however, that brands like Ella’s Kitchen can overtake Heinz to become the largest baby-food brand in the UK within 15 years of launch, Big Food cannot afford to rest on its laurels.

New generations of consumers are increasingly seeking out brands that speak to their values with products that tread lightly on the planet and offer the benefit of free-from or healthier ingredients. Old brands struggle to innovate around these pillars, so perhaps the lesson here is to think more like a Victorian parent and employ a team of qualified intermediaries to do the child-rearing for them. Providing funding to support those young charges over several years, under the guidance of those qualified in building from the ground up within the sector, could be the solution to building a portfolio of innovation that can scale over time to earn its place at the top table.